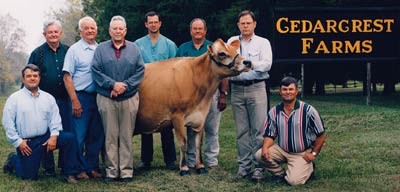

A Tradition of Excellence

Around every corner at Cedarcrest Farms in Marengo County are reminders of a dairy farming heritage that spans eight decades and four generations of the Rankin family.Photographs of champion dairy cows hang on the walls of the small, red-painted office where 10-gallon milk cans once sat awaiting transport to a nearby bottler. And just a few yards away, Cedarcrest’s latest bull prospect rests in the original 40-cow barn where workers once milked the herd by hand.It is certainly more than the late A.G. Rankin could have imagined when he began milking Jersey cows in 1919. No one is quite sure how many cows he had, but the family says Mrs. Rankin pumped water for 16 cows the afternoon before her oldest son was born.Today, that herd has grown to 1,100 cows, and Cedarcrest Farms is considered one of the finest Jersey dairies in the world.A.G. Rankin’s youngest son, William, credits his brothers, Amzi (who passed away last year), John and Joe, for much of the family’s success.”Our family has been blessed with good cow men. My older three brothers knew what we needed to have, and they’ve worked to breed good cows with good udders,” William said. “We don’t have the highest producing herd in the U.S., but everybody that’s bought cows from us has been pleased.”Sales held at Cedarcrest Farms in 1999 and 2001 were a testimony to the Rankins’ knack for breeding world-class Jersey cattle. In 1999, almost 100 buyers made the trip to Faunsdale to purchase heifers, cows and bulls for herds in 26 states as well as Canada and Brazil. Two years later, 50 buyers were on hand for the Rankins’ second sale–bringing the farm’s two-year sale total to 600 head.What draws folks from around the world to this west Alabama farm? The answer can be found in the framed, 8×10 glossies that decorate the walls of the Cedarcrest office.

Take Generators Topsy, for instance. To the average visitor, she was a long, deep-bodied light-brown cow with a black nose and bulging milk bag. But to those in the Jersey breed, she was the 1973 U.S. National Grand Champion and the first Jersey cow ever to receive a score of Excellent-97%. Perhaps the most famous Jersey ever bred at Cedarcrest, though, was Duncan Belle, who was voted the best cow of all time in the American Jersey Cattle Association’s Great Cow Contest.Extraordinary cows like Generators Topsy and Duncan Belle–along with more than 30 bulls the Rankins have placed in artificial insemination programs–have earned the family a reputation for raising top-quality seedstock. John Rankin is quick to point out, however, that Cedarcrest Farms is still a working dairy.”You can’t sell enough cows to make a living,” he said. “If you’re not profitable making milk, cow sales and the rest won’t make up the difference.”Fortunately, the Rankins also excel when it comes to producing milk. Although Southern herds typically don’t produce as much milk as dairies in other parts of the country, Cedarcrest Farms manages a very respectable rolling herd average of 13,500 pounds of milk per cow, per year. And while Holstein dairy herds often boast of higher milk production, John said Jersey milk is superior in terms of butterfat and protein.”Jersey milk has about 1.5 percent more butterfat and about 25 percent more protein,” he said. That makes Jersey milk the preferred choice of some creameries–including Mayfield Dairy, which proudly features a Jersey cow on its ice cream products. The higher butterfat content also can mean a higher price for producers. But in the mid ’90s fluid milk prices dropped so low, the Rankins began looking for new ways to market their milk.They joined forces with other west Alabama dairy producers and purchased a cheese plant in Uniontown that originally had been built by Kraft in the 1930s. “When we bought the cheese plant, fluid milk prices were down, and we could have taken our milk and put it into the cheese plant and made more money,” John said.Ironically, the price of fluid milk quickly rebounded, and by the time the plant was operational, cheese prices were so low the Rankins could no longer afford to use their own milk. Today, John’s son, Pat, and grandsons, Patrick and Brooks, operate the plant using surplus milk often purchased from out of state. The Rankins’ efforts to enhance the profitability of Cedarcrest Farms, however, are not limited to the cheese plant. They also have upgraded their two milking parlors. John’s other son, Jim (who also is a veterinarian and the farm’s chief mechanic), operates the No. 1 dairy, while Joe’s son, Jody, operates the No. 2 dairy. William explained that both milking facilities were renovated based on the research of the younger Rankins.”Jim and Jody took a camera with them to California and found two systems that could fit into our buildings,” William said. “In the No. 1 dairy, we have a double-12 parallel system, and in No. 2, we have a double-9 California walk-through.”The Rankins said both setups allow them to milk more cows in a shorter period of time, but they have been especially impressed with the California walk-through design. Because the cows come and go individually without having to turn or walk through special gates, William said Jody and his crew can milk about 40 cows per hour more than in their old parlor. Meanwhile, Jody’s brother, George, helps keep both parlors running by managing the farm’s calf and replacement heifer operations.In addition to improving Cedarcrest’s milking facilities, the Rankins have invested in their feeding and waste management programs. William, who is responsible for the row crops, is installing drain tiles in the soggy, prairie fields where the Rankins grow much of their 700 acres of corn. Thanks to the tiles, William said he has not missed a corn crop in 25 years on the field where he first installed drains.The Rankins grow about 25 percent of their dry matter feed, including a healthy supply of Johnsongrass. The feed ingredients are stored in large, covered bins and mixed by weight to produce a balanced ration. The cows are then fed in enormous, free-stall barns, which are equipped with roof vents, fans, misters and a flush system for handling waste. William and Jim have worked together on the waste management system, which includes a settling pit for solids and a two-stage lagoon. Unused nutrients are applied to hay fields and pastureland as fertilizer. William said the new system will help the Rankins be better neighbors and avoid future problems with Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation (CAFO) rules. He also plans to experiment with using phosphorous in the settling ponds to control odor–an idea brought back from France by his daughter, Annie.Annie, who is one of the youngest members of the Cedarcrest team, was selected for the month-long trip by the Rotary Club after graduating from Auburn University in rural sociology. At first, she was reluctant to leave the farm, but her cousin, Jim, finally convinced her to go.”He told Annie the Alps would always be there, and hopefully Cedarcrest would always be here. But this might be her only chance to see the Alps,” William recalled.In the end, Annie relented and was glad she did. Not only did she learn about phosphorous, but she also visited dairies and cheese plants. Now that she’s back home, Annie is following in Jim’s footsteps–which includes jobs like milking at 4 a.m. and cleaning out waste water lines on an irrigation unit.Despite the long hours, the 23-year-old said she’s happy to be learning the family business.”When I was on the marketing team at Auburn, I noticed that a lot of the people I met–who had graduated–weren’t very happy. Even those that had money weren’t happy,” she said. “But everytime I’ve gone to a sale or we’ve had a sale here, I’ve met good people who love what they do. Everyday there’s something new at the dairy; there’s always room to learn something. And, I love working where I live and working outside.”