Alabama BCIA’s Top Producers Share Their Success Secrets

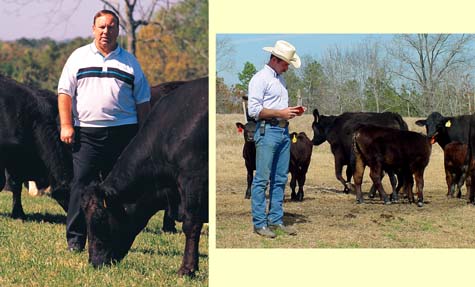

William Mayfield and Joe Navarre live on opposite sides of the state. One raises commercial beef cattle; the other raises purebred bulls. Yet these two men share a common philosophy that’s propelled them to the top of Alabama’s beef industry.Superior genetics plus good herd health and record keeping equals better calves. They have the proof.This formula earned Mayfield’s Triple M Farms the Alabama Beef Cattle Improvement Association’s (BCIA) 2001 Outstanding Seedstock Producer Award. Not to be outdone, the Navarre-managed Torbert Farms was named BCIA’s Commercial Producer of the Year.Visitors to these operations, however, wouldn’t have to see a plaque hanging on the wall to know these farms are special.From the time guests enter the gates at Triple M in Bibb County, they are surrounded by rolling, lush pastures, dotted with strong, healthy looking Simmental cows and calves. Mayfield, who’s been in the cattle business for 25 years, said he had one goal when he started raising purebred cattle in 1983.”I wanted to build the best brood cows I could put together,” he said. “Over the years, I’ve put a lot of time, money and research into not only our cows but also the bulls we use.”Today, the Triple M herd includes 100 purebred, black Simmental brood cows. In recent years, the farm–named in honor of Mayfield, his wife, Terri, and son, Cameron–has produced some of the top-indexing Simmental bulls at the North Alabama, Auburn and West-Central Alabama bull tests. Most of Mayfield’s bulls, however, are marketed through the Sunshine Bull Development Program or sold by private treaty. His females are marketed in Simmental consignment sales throughout the Southeast.Although Mayfield strives to produce only black, polled cattle, he was initially reluctant to emphasize color in his selection program.”I bred red cattle for 15 years and pretty much was hesitant to breed black,” Mayfield said. “Demand got so great we had to. Customers started calling and requesting black cattle. That’s all they wanted.”Mayfield started raising black Simmental cattle in 1995 and has built his herd gradually until all his cows are black (or red cows that when bred to a black bull will produce black calves). Mayfield said it just makes good business sense to raise black calves because solid-colored cattle–especially black–are bringing a higher price.Still, he didn’t jump on the black-cow bandwagon blindly. Mayfield said he studied the genetics of popular black Simmental bulls and then bred his cows (using artificial insemination or AI) to bulls that not only were the “right” color, but ones that also had strong growth and maternal traits. Mayfield has been equally discriminating in his selection of cows. Three M was fortunate, he said, to acquire some extremely good genetics through dispersal sales when other farms went out of business. In addition, he keeps detailed records that assist him in knowing which cows to cull and which ones to keep.”You can’t look at them and tell if they are going to raise good calves,” Mayfield said. “You have to have good records.”Triple M tracks the performance of its cattle using the American Simmental Association’s Total Herd Enrollment (THE) program. Mayfield also started using ultrasound to gather carcass data on his bulls and heifers.On the other side of the state, Joe Navarre is just as committed to record keeping at Torbert Farms in Lee County. Since taking over management of the operation six years ago, Navarre has tripled the size of the cow herd and shortened the calving season by more than 60 days. He also has built a top-notch working facility.”It makes a big difference if you have the correct working facilities,” Navarre said. “It speeds your efficiency so much. If you can go out there and weigh all your calves in an hour versus three hours, you’re much more likely to go out there and get your weaning weights.”The commercial beef cattle operation now includes 230 Angus and Angus-crossed females. Each year, frozen embryos are implanted into about 50 of those cows to produce calves for a local purebred producer. The estrus cycles of the remaining cows are synchronized, and they are bred using artificial insemination. Those that don’t conceive are bred to Simmental or Angus bulls purchased from top Alabama BCIA producers. Besides caring for its own cattle, Torbert Farms backgrounds steer calves for other producers and manages the Piedmont BCIA Heifer Development Program.

Records for Torbert Farms are maintained using the Nebraska cow/calf computer program, but Navarre soon will be switching to the BCIA-promoted Red Wing software. Both programs track the performance of each animal, and provide detailed financial reports.Navarre uses this data to identify his top heifers, which he then sells as replacements through BCIA heifer sales and by private treaty. The computer system also helps Navarre identify cows that should be sold because they either did not wean a calf, or they had a calf with a low weaning weight.Navarre credits BCIA’s promotion of record keeping, performance testing and marketing for improving Alabama’s beef industry.”The BCIA has given us the tools to help us stay competitive,” he said. “If you look at the cattle business today, it’s changing fast and you’ve got to change with it to remain profitable.”Torbert Farms markets its steer calves in truckload lots through the Piedmont Marketing Association each fall. By shortening the farm’s calving season, Navarre has been able to put together uniform groups of cattle, which buyers prefer. In addition, his strict culling standards and emphasis on genetics has helped him increase the average weaning weight of his steers from 435 pounds to 548 pounds.”Being able to sell a uniform calf crop is very important,” Navarre said. “Buyers are looking for uniform calves, color wise as well as height and weight. That’s where you can get the most for your calves. If you can sell a uniform group of calves, you can make five to 10 cents more per pound.”