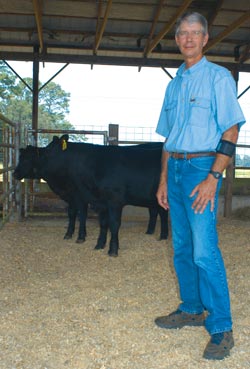

Bovine Boot Camp

Cattle farming may not be rocket science, but Randall Rawls says it’s not far behind.”It’s very much like all of agriculture — beef production is getting to be a very complicated science,” said Rawls, superintendent of Auburn University’s Upper Coastal Plains Agricultural Research Center outside Winfield. “The days of having just a few cows and a bull out in the pasture and going out and looking at them every now and then and harvesting the calves is a thing of the past. “Now, the producer has to pretty much know what kind of quality his cattle are as far as what kind of performance he’ll get in weight gain, what the carcass quality is, and he has to select his bulls primarily to breed toward the end point that he’s aiming for. We’re in the business of marketing a food source, not just marketing cattle,” Rawls said.That’s why 13 of 123 heifers from the Ag-O-Rama BCIA Heifer Sale on Aug. 27 never left the experiment station, but instead became the newest recruits in a sort of bovine boot camp for would-be mothers. As the latest candidates in the Leading Edge Heifer Development & Evaluation Program, a coordinated effort of the AU substation and the Alabama Cooperative Extension System, these heifers will remain at the substation farm where they will be tested and tended, fed and bred, pampered and palpated until late March or early April. If all goes well, they’ll go home as expectant first-time mamas.About 400 heifers have gone through the 5-year-old program, the brainchild of Sam Wiggins, a county extension coordinator in Pickens County. Owners pay $260 per heifer to enter the program which seeks to educate beef cattle producers in west Alabama and east Mississippi on advancements in raising better cattle. It also serves to demonstrate feeding and health programs that result in heifers that are successfully bred and calve at 2 years old. Meanwhile, farmers learn how genetic traits such as pelvic size, reproductive tract scores, disposition, structure and frame all factor into fertility within beef cattle.”The program is set up to be educational, to aid in educating the producers as well as offering a service,” said Rawls. “There are several ways of doing the same thing, and that’s not to say that what’s being done on individual farms is a wrong way because it’s not. As long as he comes up with the end product, his way may be better. And there are a lot of good cattle producers in Alabama.”But not every farmer has the time, funds or resources to manage a successful heifer operation.”The program allows producers to have someone else manage their heifers without them having the labor involved in getting those females bred,” said Perry Mobley, director of the Alabama Farmers Federation’s Beef, Dairy and Hay and Forage Divisions. “And they can get those cattle bred in a better genetic package than they can afford to purchase. … It’s both convenience and cost — convenience in not having to manage the heifers and cost in that you are breeding them to a bull most people would not be able to afford. Also the genetics that you get out of the deal, the calves, are going to be a more desirable genetic package than you normally would have just by turning a bull out.”That’s why John Bambarger of Northport has put 44 heifers through the program over the past couple of years. In fact, two of the heifers he offered at the Ag-O-Rama sale were products of the program two years ago.”The big advantage for us was we were getting top quality heifers that we could use for replacements,” said Bambarger, who runs a 457-acre cattle farm in Eutaw with his brother Jim. Bambarger said he has two good herd bulls on his 70-75 cow-calf operation, but keeping 20 replacement heifers back would force him to buy another $3,500 to $4,000 bull just for them. “It just wasn’t a convenient thing to buy a bull just for that small group of replacements. … Plus, managing a group of young heifers separate from your cowherd just means one more management requirement. It was just easier.”And cheaper. Instead of buying another bull, Bambarger got the benefit of the experiment station’s three Black Angus bulls, which Rawls described as “probably better than what the average cattle farmer in the state of Alabama could afford.”Rawls said the bulls, all known for siring low birth-weight calves (an important consideration for the young, first-time mothers), are of the highest quality he could find. “We want as much growth in these bulls as we can get without compromising birth weight,” said Rawls. “We’re also looking at milking ability because we want the heifer calves produced from this mating to make good mamas. And we’re also looking at carcass quality — leaner carcasses, more muscling, larger rib eyes … the ideal situation is USDA Choice. That’s the kind of thing we’re shooting for.”That’s also what Bambarger is shooting for. “This is not a hobby,” he said, adding that he took early retirement from his job as an electrical engineer with Alabama Power Co. to raise cattle on the family farm.Of course, things have changed since his father raised cattle. And Bambarger, the former engineer, has had to become a neophyte geneticist of sorts. He’s learned he has to stay abreast of technology. He has to know about EPD (Expected Progeny Difference) numbers, a numerical ranking based on the prediction of how future offspring of each animal are expected to perform. He has to know about things like calving ease, marbling and percent retail product EPD.”Dad was pretty progressive. He’d use everything available to him, but this kind of stuff wasn’t available years ago,” Bambarger said. “The only criteria he had to go on was to look at the bull’s father to maybe get an idea of what the offspring would be. Now, half of a bull’s evaluation is based on his EPD numbers and so on. “You have to understand that stuff. You have to understand EPD numbers — maybe not how they’re calculated but how they’re used and what kind of weight to give them. It’s not the only decision-making criteria, but it’s a significant part of it. You have to believe it.” For more information call the Upper Coastal Plains station office at (205) 487-2150.