Chicken Litter: Answer to Sky-High Propane?

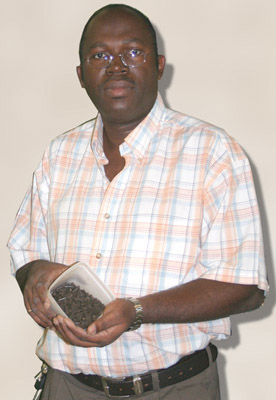

Unlike the fabled alchemists of old, Dr. Oladiran Fasina has never turned lead into gold. But the Auburn University assistant professor is one step closer to turning chicken litter into cold, hard cash.Or, at least, Alabama’s poultry farmers — with anywhere from 1 to 2 million tons of litter to contend with annually — are hoping that’s the case.A year after receiving a $50,000 grant from the Alabama Department of Economic and Community Affairs, the AU biosystems engineer is confident that poultry litter, a mixture of manure and bedding material, is the perfect solution to the record-high fuel costs faced by poultry growers.The first stage of the project was to demonstrate that it’s possible to burn poultry litter for heat. That alone was no easy feat, considering litter’s dusty, granular makeup (high in ash and moisture content) makes it difficult to burn.Fasina overcame that by first turning the raw litter into compact pellets that would feed easily into a furnace that heated a greenhouse on the university’s campus. He also pelletized peanut hulls and switchgrass.But because the cost of pelletizing is so prohibitive (about $45 per ton, not counting the cost of transporting the bulky material) the next step is to show that it can be done affordably.”Ultimately, what I see happening is a burner outside the chicken house,” said Fasina. “The poultry farmer will collect the litter from the poultry house, store it somewhere on the farm and then, when it’s time to use it, just use a forklift or a dump loader. It’s like a recycling center. You don’t have to transport it anywhere to make it into pellets. You just use it on-site on the farm.”Fasina isn’t alone in his thinking. Researchers throughout the world see poultry litter as a possible renewable energy source, although not always in the same way. While some work at developing a furnace capable of burning raw poultry litter, others are exploring converting poultry litter into ethanol or electricity.”It’s being done,” said Dr. David Bransby, an agronomist who has worked with Fasina on the litter-to-fuel project. “The primary problem is that it doesn’t make economic sense, and the reason is the capital cost of the equipment is too high. We can pelletize, and you can use pellet stoves, but making those pellets is not a cheap process. It takes energy to do it. That’s one of the problems — every time you handle a material, it costs you money.”According to data compiled by Auburn agricultural economist Gene Simpson, it cost more than $5,800 to heat a single Alabama poultry house in 2004 — up 49 percent from a year earlier, 107 percent from five years earlier and 383 percent more than it did in 1994. That means a grower with four 40-foot by 500-foot houses forked over $23,200 for propane in 2004 — $8,400 more than he/she did in 2003. What’s worse, those calculations were based on an average propane price of 91 cents per gallon, not the $1.25 to $1.30 or more that growers are likely to pay this year.”Obviously, there is much variability, depending on number of flocks, geographical location, type of house (solid, insulated walls vs. curtain), and weather,” said Simpson. “But the bottom line to me is that the price of propane increased around 30 percent this fall, and a large number of growers, especially in the southern counties, were not offered a fuel contract. That means that virtually every grower had his fuel bill increase by 30 percent or more, and fuel is, by far, the largest out-of-pocket expense a grower has.”The good news, however, is that the potential savings from using poultry litter as fuel are enormous.According to Bransby, poultry litter varies in composition but averages about 5,000 British thermal units per pound. Using that as a standard, he calculates that a ton of litter will provide about 10 million Btu, compared to 90,000 Btu per gallon of propane. At $1.20 per gallon, Bransby figures propane heating is more than 13 times more expensive than using the energy in chicken litter.”The challenge is to convert the litter efficiently to heat and power,” said Bransby. “But we can actually be pretty inefficient and still come out ahead with this difference in the cost of the raw material.”Fasina’s research found similar savings. When compared directly to “natural gas only,” poultry litter pellets led to cost savings of $4.91 per day in heating the 24-foot by 96-foot greenhouse. That did not include equipment and raw material costs.Guy Hall, director of the Alabama Poultry Producers division of the Alabama Farmers Federation, says recycling poultry litter as heat can only improve growers’ bottom line.”Once scientists perfect the use of alternative fuels to heat poultry houses, we will be able to positively affect the producers’ bottom line,” said Hall. “When farmers are able to use poultry litter in combination with other fuel sources for heating, they will be utilizing a resource already on the farm and lessen their dependence on petroleum products.”In the meantime, Fasina says Alabama — with 22 million acres of forestland and 6 million acres of grassland and cropland — is rich in resources for generating alternative energy. “Based strictly on the agricultural and forestry sectors, Alabama has enough raw biofuel to provide the electricity for all the residents in the state,” said Fasina. “We’re importing coal from Wyoming because it’s a cleaner coal that’s lower in sulfur than that mined here in Alabama, and we do it partly because of EPA regulations and because it’s cheaper.”Perhaps even more important, says Fasina, is how we are going to dispose of the tons of litter created each year in Alabama.

Auburn’s Simpson says it’s really difficult to gauge just how much litter Alabama poultry growers produce each year. “We really don’t have a good handle on it,” said Simpson. “However, the trend over the past several years has been to increase the number of flocks between cleanouts. It used to be that nearly every house was totally cleaned out about once a year. In the past few years, more and more growers are simply removing the small amount of wet, caked litter and occasionally top-dressing with fresh shavings between flocks. They’ve found that they can wait 2-4 years or more between complete cleanouts if they better manage their litter through improved ventilation management.”Several years ago, we ‘guesstimated’ that Alabama generated about 1.5 million tons of litter per year. Some agronomists even thought it might be approaching 2 million tons. With the changes, I would be more inclined to believe 1 to 1.2 million tons per year,” he added.Regardless of how much litter is produced, generations of poultry farmers have used litter from their poultry houses as a cheap fertilizer, simply spreading it on their pastures and fields. But in recent years, increased regulations have limited when and how much litter may be applied.”From an environmental point of view, it’s becoming more and more difficult to get rid of the poultry litter,” said Fasina. “I don’t think we have any option but to find a way to use it on the farm, and the easiest way is to just burn it as a source of heat. That’s the easiest way.”