CORN OF PLENTY: If Weather Holds, A New Crop Could Be King

For 40 years, Ronnie Holladay’s crop of choice was cotton. No more.This spring, driven by the nation’s push toward ethanol, the long-time Lowndes County cotton farmer hopes to turn fields normally blanketed in white cotton into lush, green rows of corn.”We are getting away from cotton,” Holladay said. “We’ve been in the cotton business for a lot of years, but we see the potential in other crops more than cotton. So, we’re phasing out our cotton operation, and going more to corn as a lot of people are.”Holladay’s right — everywhere, or so it seems, farmers are turning to corn.In fact, if weather permits — and that’s a big “if” — 2007 will likely be remembered as the year corn became king all across America. The appetite for ethanol as an alternative to Middle Eastern oil has pushed corn prices to $4.30 a bushel, the best price since the $3.58 farmers received in 1996. As a result, the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service has forecast a 15 percent increase as American farmers plant 90.5 million acres of corn — the most since 1944 and 12.1 million more acres than last year.In Alabama, corn fever is even more obvious. NASS forecasts a 50 percent jump in the state’s corn production as farmers plant 300,000 acres — 100,000 more than last season. Much of that acreage will be on land once dedicated to cotton, which is expected to see a 22 percent decline to 450,000 acres. Peanuts are also expected to decline about 3 percent to 160,000 acres. Soybeans, buoyed by good prices, are expected to see a 19 percent increase from last year, up to 190,000 acres.Alabama’s winter wheat acreage is estimated at 130,000 acres — 30,000 more than in 2006. Hay acreage intended for harvest at 900,000 acres, is up 25 percent from last year. Sorghum production is expected to remain unchanged from 2006 at 10,000 acres, and sweet potato intentions are 2,500 acres, just 100 more than last year.”The farmers are trying to decide which crop they can have the hope of making the most money for,” said Charles Burmester, an Extension agent based in Belle Mina. “And right now, cotton prices haven’t moved much at all. We’re still in the low 50-cent (per pound) market for cotton, and it’s really hard to pencil a profit with those kinds of prices.””It’s all economics,” said Stuart Sanderson of Limestone County. “With corn at $4 a bushel, you can make 65-bushel corn do the same thing that you can with 600 pounds of cotton at 52 cents.”No wonder Sanderson planted 1,400 acres of corn and no cotton this spring. “That’s more than double the biggest corn acreage we’ve ever had,” he said. “Everywhere you look, biofuel is driving the price of corn and the increased acreage because we’re coming off the second-largest corn yield in U.S. history, and the prices are still good, and it’s all being driven by ethanol.”That’s why you’ll see Dennis Bragg switching from cotton to corn on 2,000 acres in Toney, and why Herman Rochester of Leesburg will plant 1,800 acres in corn.”Higher corn prices have definitely influenced producers’ decisions to add more corn at the expense of cotton acres, especially with the relatively flat cotton prices,” said Buddy Adamson, director of the Alabama Farmers Federation’s Cotton and Wheat and Feed Grains Divisions. “An additional gain from the additional corn acres is the rotation benefit from cotton to corn, which some producers have probably wanted and needed on any continuous cotton ground they may have been working. I think the lack of rain thus far will be the determining factor on final planted corn acres.”Burmester said the interest in corn is stronger in north Alabama than the lower half of the state where sandy soils and a lack of irrigation systems make dryland corn a riskier proposition. “It becomes dry much quicker down in south Alabama, so I don’t think there’s as much interest in corn down there as there is up here,” he said. “I don’t think their switch in acreage will be anywhere near as dramatic as it is up here.”

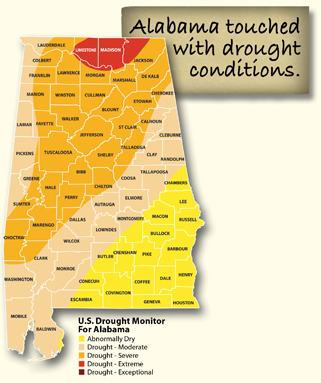

Of course, the crop that would be king must first survive one of the driest springs in more than a century. The Tennessee Valley Authority reported the driest December-January-February span in 117 years of recordkeeping in the TVA’s seven-state region that includes parts of north Alabama. Time will tell whether the April 1 showers that stretched across the state will be sufficient for a time, or simply a cruel April Fool’s joke.”Dry weather is just discouraging,” said Heath Potter, a regional Extension agent based in Moulton. “We’re not talking about dry weather in July and August that we’re used to — we’re talking January, February and March. Normally, we’re trying to figure out how to get crops into the ground between rains. This year, we’re trying to decide whether to plant before we get a rain or to wait until it comes.”The lack of rain has been particularly discouraging for those making the switch from cotton, which can withstand dry spells better than corn. “One farmer I visited with told me that if it didn’t rain by the middle of the next week, he was sending back 1,200 acres of corn seed,” said Potter. “He had not planted corn on that family farm in decades, and he wasn’t going to take a chance on putting 1,200 acres of corn in the ground without knowing what was going to happen.”Sanderson, however, was more fortunate than most. He was able to begin planting on Feb. 27, and by late March, was pleased to see that it was faring well despite a lack of spring rains. He’s so certain of corn’s role in America’s energy future that he’s among the principal investors in what will become the state’s largest ethanol plant. That’s also why six months ago he invested in the farm’s grain storage, raising its capacity from 25,000 bushels to 165,000. It was obviously a wise decision since the increased corn acreage is almost certain to cause a shortage in available storage. “I have several neighbors who’ve switched a lot of cotton acreage into corn, and have built grain bins or secured leases on grain bins that aren’t being used on other farms,” said Sanderson. “You can buy bins now, but you can’t get anybody to put them up. The crews to erect these bins are scattered. It would be hard to get one put up now in time to use it. I’ve heard about farmers converting those old blue silage bins into storage, and there are people going around trying to sell these bagging systems. So, every possible place where corn can be stored this year it’s going to be stored.””I keep hearing farmers talk about all this corn they’ve got booked, but where are they going to store it?” asked Potter, who added that the time may be right for the Extension system to hold some stored grain management workshops to help combat moisture, insect and disease problems. Ironically, some solutions for storage could come from cotton gin operators. The decline in cotton acreage could mean another tough year for the gins. “If there’s a short cotton crop, the gins could really hurt because a lot of them have updated, put in new presses, new module feeders,” said Sanderson. “The fear is that a short cotton crop could have a serious impact on a lot of gins across the Midsouth.””One of the gin managers in my area said he was going to keep his eye real closely on this corn market,” said Potter. “He was going to consider building a corn storage facility on site with the cotton gin. He said he wanted to make sure first that this corn production is not just a fad that’s going to end in a year or two.”Burmester says it’s not all bad news for cotton. Planting corn on cotton land is a good rotation, one that will help reduce reniform nematodes should the time come to plant cotton again. And although Potter expects a 40 percent decline in cotton in his area, he said no one should count cotton out just yet. “This is cotton country up here,” Potter added. “We are not going to get completely away from cotton, I can assure you that.”