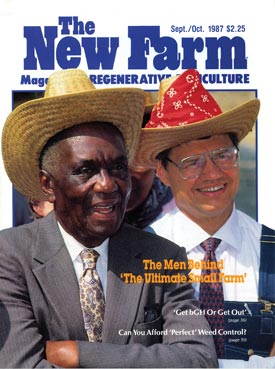

Dr. Booker T. Whatley: His Seeds and Ideas Are Still Taking Root

“The evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones.”

— William ShakespeareOne thing is for certain. Shakespeare never met Dr. Booker T. Whatley.For though the world-famous horticulturist passed away Sept. 3 at his Montgomery home, his revolutionary ideas are bearing fruit (and vegetables) on small farms everywhere.Neighbors interviewed Whatley not long before his death, and while the 89-year-old’s body was weary that day from a diabetic episode, his mind was sharp. He talked of growing up in Calhoun County, of attending Alabama A&M University and of serving in World War II and Korea. With vivid detail, he recalled how he landed an assignment to work on a hydroponic farm in Tokyo and how the scientist hired to run the place convinced Whatley to earn a doctorate in horticulture from Rutgers University.During that Neighbors interview, Whatley spoke of the people who impacted his life and of those touched by his own work. Chief among Whatley’s supporters is his wife of 56 years, Lottie, a woman known by many as a gracious Southern lady.While Whatley was not known for his romantic prose, he honored his Lottie in a way befitting a horticulturist — he named the “Foxxy Lottie” grape for her. He also developed 15 varieties of muscadines during his career.But it was his yellow-meated Carver sweet potato (and other sweet potato varieties) that Whatley hoped would revolutionize Southern agriculture. “We could grow sweet potatoes (for animal feed) in the South, but we couldn’t grow corn and be competitive with the Midwest,” Whatley said as he recalled his research. “With sweet potatoes, Alabama could compete with the Midwest in carbohydrate production, but it never did catch on.”Most of Whatley’s ideas, however, did catch on — some like wildfire. History has proven that Whatley was truly ahead of his time. Take, for instance, some of the topics covered in his 180-page book, “How To Make $100,000 Farming 25 Acres,” which was published in 1987 by the Regenerative Agriculture Association. Almost 20 years ago, Whatley was writing about U-pick operations, community supported agriculture (CSA), drip irrigation, rabbit production, farmer-owned hunting preserves, kiwi vines, shiitake mushrooms, veneer-grade hardwood stands, on-the-farm bed and breakfasts, direct marketing, organic gardening and goat cheese production. What’s even more astounding is that he was advocating many of these ideas in the 1960s and ’70s.Today, Whatley’s ideas read like the editorial calendar of a mainstream agricultural magazine. But 30 years ago, Whatley’s work challenged the teaching of many in the land grant university system.Despite the skeptics, Whatley continued to live by his motto: “Find the Good and Praise It.” He even published a Small Farm Technical Newsletter to share the success stories of small farmers. At its height, the newsletter had more than 1,000 subscribers, many of whom earned a comfortable living on limited acreage despite conventional wisdom that said farmers had to “get big or get out.”One unlikely convert to Whatley’s philosophy of farming was Tom Monaghan, former president of Domino’s Pizza and owner of the Detroit Tigers major league baseball team. Monaghan contacted Whatley in 1984 after reading an article in the Wall Street Journal titled “Booker T. Whatley Contends His Program Will Help Small Farmers Make Big Money.”Monaghan was so intrigued by Whatley’s ideas that he invited the researcher to visit the Domino’s headquarters in Ann Arbor, Mich. Three years later, the pizza tycoon and visionary horticulturist stood side by side as they dedicated the Booker T. Whatley Farm at Domino’s Farms.The farm was a thriving testimonial to Whatley’s work, incorporating many of the ideas the Alabama native had long espoused. It included everything from blueberries, honey and lambs to Christmas trees, venison and a catch-your-own fish pond. It was designed to not only supply mushrooms and other products for Domino’s franchises in the Michigan area, but also to market food products to Domino’s employees through a Clientele Membership Club — similar to today’s Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) farms.Most importantly, Monaghan wanted the farm to be a laboratory where Whatley could further develop his ideas with the ultimate goal of regenerating 100,000 small farms by the year 2000. Unfortunately, Whatley Farm never reached its full potential because Monaghan sold his stake in Domino’s, and without his guidance, the focus of the farm was shifted away from Whatley’s original plan.On thousands of other farms around the world, however, Whatley’s ideas have taken root and are thriving. Some farmers learned of his work during the 12 years Whatley served as a professor at Tuskegee University. Others heard him lecture as a visiting professor at Cornell University, the University of Maryland and the University of Florida.Still others were inspired by one of the 20 speeches a year he gave throughout the country. Whatley even shared his knowledge abroad, thanks to an arrangement with the State Department that allowed him to advise sub-Saharan African countries about sustainable agricultural practices.Whatley received the Alabama Farmers Federation’s Service to Agriculture Award in 1974 and was the first African American elected as a fellow in the American Horticulture Society. Despite all of the accolades, however, Whatley was a farmer at heart. Until recent years, he had a bountiful garden at his home just off of Court Street in Montgomery, and could often be found there dispensing produce and wisdom to visitors.Never one to mince words, Whatley was quoted in his book as telling farmers, “If you can’t or won’t observe the basic laws of horticulture, then forget it. Either do it right, or don’t do it at all, because the results just won’t be what you wanted. You’ll simply be wasting your time and money.”Beyond those basic laws, Whatley believed that there are untapped opportunities for small farmers to make money. But he also understood that farmers are innovative and independent by nature, and encouraged them to use their common sense.”Nobody that I know of is following my concept 100 percent,” Whatley wrote. “I don’t think there ever will be. I hope not. Americans are independent and farmers are even more independent than most of us.”If everybody started doing just what I say, it would mean that they aren’t using their heads enough and coming up with enough ideas of their own. They’d be relying too much on someone else’s formula or recipe. That’s just what got farmers into a lot of the trouble they’re in today.”That said, it’s hard to deny the contributions Whatley made to agriculture, and it’s certain that the good he did will live after him. As for us at Neighbors, this look back on the life of Dr. Booker T. Whatley is simply our effort to follow his motto — to find the good and praise it.