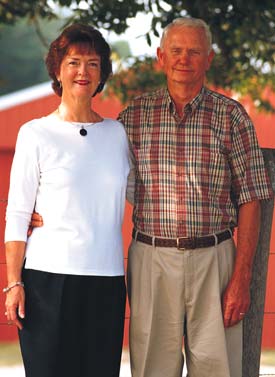

Farm of Distinction – One Man’s Vision For Success

From a lush hilltop in one of his Chambers County pastures, Charles “Buddy” Burton, 69, can behold the result of 48 years of hard work, wise investments and meticulous management.To his left, plump cows graze in the shadow of trees that will provide income for his family for years to come. Below, an overflowing hay barn flanks the dairy parlor where Burton and his brothers once helped their father milk cows. And in the valley below, Buddy and Lynda Burton’s beautifully landscaped home lies at the end of a long drive marked by a sign that proclaims Burton Farms as the Alabama Farm-City Committee’s 2002 Farm of Distinction.As this year’s winner, the Burtons received $1,500 and will compete for the Lancaster/Sunbelt Expo Southeastern Farmer of the Year award at the Sunbelt Expo Oct. 15-17 in Moultrie, Ga.For Burton, the farm is the realization of a dream that began when he was just a boy.”I was born and raised on the farm, and I always liked it,” Burton recalled. “I joined the Navy and hadn’t been in very long when I realized exactly what I wanted to do when I got out–that was to farm.”Burton bought his first 172-acre parcel of land in 1953, a year before he completed his tour in the Navy. In the years that followed, he raised cotton and ran a logging operation before settling on a farm plan that focuses on beef cattle and forestry.Through the years, Burton expanded his farm operation through timely purchases of land and through the inheritance of family property. Almost a half-century later, the self-described conservationist owns 1,700 acres, including 1,200 acres of forest.”He’s a natural-born son of the land,” said Lynda. “He loves watching things grow and managing the land to its fullest potential.”It was that love of the land, Burton said, that led him into the cattle and timber business. After struggling for years to control erosion in the small fields where he farmed, he decided to convert much of it to pasture.Today, Burton has a 260-cow beef cattle operation. He attributes much of his success to good management, which includes a controlled breeding program.”Anybody in the cattle business should have a controlled breeding program,” Burton said. “We have a 90-day calving season that begins Nov. 1 and ends around Feb. 1.”Although Burton once used Hereford bulls on his Angus-crossed cows, he now uses strictly Angus bulls, which he purchases from local breeders like Dr. Tom Lovell of Lee County and Byron Welch of Lafayette.In addition to selecting bulls with superior maternal and growth genetics, Burton also maximizes his forage production through rotational grazing and good management practices. He soil tests his pastures and hay fields every three years and applies fertilizer according to the test results.”In 2000–when it was so dry–we didn’t give out of grass, but the cows were on the last grass I had when it rained. We wouldn’t have done as well had it not been for our rotational grazing program,” Burton said. In addition, Burton reduces his dependence on hay by overseeding his pastures in the fall.”One of the best tools we’ve bought was a no-till drill. We use it extensively in the fall to overseed about 300 acres of pastureland with ryegrass,” he added.During calving season, Burton is a “vigilant watcher,” according to Lynda. She said he works hard to ensure all his calves are promptly vaccinated and wormed. Burton also keeps detailed records about each birth, which helps him cull unproductive cows.Burton markets his calves in lots of 40-50 at nearby Roanoke Stockyards. He delivers the calves to the auction barn the day before the sale, and they are weighed and sorted. The cattleman says that saves him money due to “shrink,” or weight loss that can occur between the time the calves leave the farm and when they are sold. He then gives buyers a 2 percent “pencil shrink” to compensate them for weight loss that occurs during shipping.The Burtons said this system of marketing has been profitable for the farm in recent years, but they also remember times when cattle prices weren’t so good.”One year we went all out on stocker cattle, and prices fell drastically,” Lynda recalled. “We paid 80 cents (a pound) in the fall, and by the next May, we took 38 cents for them,” Burton interjected. “I remember watching the loaded trucks go down the road as I stood at the bedroom window with tears rolling down my face,” his wife recalled.The Burtons survived that marketing disaster thanks, in part, to their forestry operation, which actually began when Burton’s father donated topsoil for the construction of a road near the farm.Burton recalled that his father gave him the barren hillside where the topsoil had been removed, and the youngster planted five acres of pine trees under the guidance of 4-H Club Agent Robert Horn. In the years that followed, Burton purchased additional forestland, which he managed for pine and hardwood production as well as for wildlife.”We started leaving oak and hickory hardwood thickets for the deer and turkey,” Burton said. “We’ve always managed all of our timber land to the best use of the land–whatever that might be.”In addition to managing established timber stands and pine plantations, Burton also operated a small logging business until the mid ’80s. Today, the Burtons’ 1,200 acres of forestland includes 300 acres of planted pines and 400 acres of timber in the Ridge Grove community that Lynda inherited from her father, George Veazey Langley.The Burtons share the credit for their successful forestry operation with the foresters who advised them over the years, the lenders who had faith in them, and their son, Charles, who now operates his own forestry business, Burton Logging.”We can’t emphasize enough how important our son has been to our farm,” Lynda said. “From the time he was 7, he was driving a tractor and working on the farm–not because he had to, but because he wanted to. We would not be where we are today without his assistance.”Lynda, who stayed home with the children during their formative years, now teaches middle school English at nearby Five Points Elementary School. She said raising the children on the farm taught them a good work ethic and has helped them “become productive, eager workers.”The Burtons’ son, Charles, and his wife, Allison, have three children, Brittany, Brooke and Jake. Their daughter, Camille Mentzer, and her husband, John, live in Marietta, Ga., where she is a flight attendant and he is a pilot. And their youngest daughter, Celeste, is a teacher in Hoover, Ala.Lynda said the farm has provided a wholesome lifestyle for the children, and they’ve always enjoyed working with their father. She recalled one time when Burton needed some help in the hay field and Charles and Camille drove the truck–one operating the pedals while the other steered. Today, the Burtons’ grandchildren love visiting the farm, too. “The last time Jake was here he said, ‘Papa, I want to ride the John Deere tractor,'” Burton said. “I was tired and worn out, but I said, ‘Okay let’s go.’ That’s one of the high points of farming for me.”After 38 years of marriage and almost five decades of farming, the Burtons are still in love with the land and with each other. While she praised him for being a good farm manager, he pointed out that part of the farm’s success is due to her management of the household budget. They do, however, agree on one point–there’s no place they’d rather be.”When we hear ‘How Great Thou Art,’ we have a special appreciation for it because–living on the farm–we see everyday how great God is,” Lynda said.