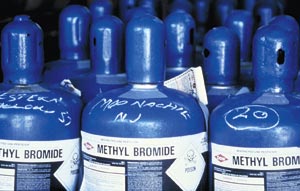

Methyl Bromide Extension Unlikely For American Producers

A decision to refuse an American request for continued use of a standby farm chemical has not only quashed the hopes of U.S. fruit and vegetable growers but may even have sealed the fate of some.Opponents of the chemical, methyl bromide, contend it is a major contributor to ozone depletion. But many farmers say it’s essential to their long-term economic survival. Under the terms of a 15-year-old environmental treaty known as the Montreal Protocol, methyl bromide would be banned from farm use in industrialized countries by 2005.Claiming no adequate alternatives are available to replace methyl bromide, U.S. farm groups petitioned for a temporary exemption. But at a technical meeting in Nairobi, Kenya last fall, negotiators representing the European Union and many poor countries refused to exempt the United States from the scheduled phase-out.Methyl bromide, a fumigant used to control insects, nematodes, weeds and pathogens in several crops, is considered by many scientists to be a principal ozone-depleting substance. Many producers, on the other hand, consider it an essential farm chemical–one that is simply irreplaceable in some instances.”There are substitutes that work in some cases,” said Dr. Joe Kemble, an Alabama Cooperative Extension System horticulturist and Auburn University professor of horticulture. “But in terms of horticultural crops–vegetables and turf, for example–there really are no alternatives.”While conceding that methyl bromide is no cure-all, Kemble said it “deals with about 90 percent of the issues growers face in turning out their crops.” Replacing methyl bromide with more expensive alternative chemicals, he said, will add hundreds more per acre in operating costs at a time when many growers are having a hard enough time keeping up with overseas competition.”When a farmer has to turn around and spend another $100 or $200 or so an acre on chemicals, it either means that he’s not going to be in business anymore or that he’s going to reach the point where there’s very little left to support his family. Everything he makes will have to go back into supporting the operation,” Kemble said. “It’s just helping him stay afloat year after year, and, ultimately, that’s just not the way to do business.”Supporters of the ban point to European farmers as proof of how quickly the alternatives can be adopted. The vast majority of these producers, they argue, would not return to methyl bromide even if they could. Besides, they contend, the exemptions not only would prevent steady progress in healing the ozone layer but would discourage U.S. farmers from adopting safer products. Kemble, for one, doesn’t buy it.”Safer? Safer for whom?” he asked. “Some of the alternatives may be safer for the ozone, but they’re actually more toxic for the people who apply these products. They require self-contained breathing apparatuses and all the other things that are associated with it.”Methyl bromide isn’t the safest farm chemical, but compared with these alternatives, you’re not required to wear any special gear or breathing apparatus to apply it,” Kemble said.As for the ozone-depleting properties associated with methyl bromide, Kemble said a number of technologies are now available that enable farmers to more effectively trap it in the soil long enough to break down before it reaches the atmosphere. New plastic mulches, for example, which are less permeable than similar products, have been shown to be effective in trapping methyl bromide in the soil and keeping it there. While the Nairobi decision technically amounted to a deferment and not a final decision on whether to grant the exemptions, Kemble fears the handwriting already is on the wall.Ironically, he said, many fruit and vegetable growers probably could weather the higher costs if American consumers were willing to pay more for produce. The problem is that most aren’t. “We simply can’t point accusing fingers only at farmers,” Kemble said. “Farmers are as environmentally conscious as the next person–more so, in fact–but they’re expected to turn out the least expensive products despite these higher production costs.”Kemble also said the argument that European growers have easily adjusted to the ban is misleading.”The fact is, European farmers have subsidies, while our (horticulture) farmers don’t. Americans need to understand that. The issues are not as cut and dry as most people think. Lots of livelihoods are riding on this. If American consumers demand a safer environment, they’re either going to have to pay more for their food until new alternatives can be found or cut losses for their farmers,” Kemble said. “Otherwise, you’re going to see fewer and fewer American farmers in business.”