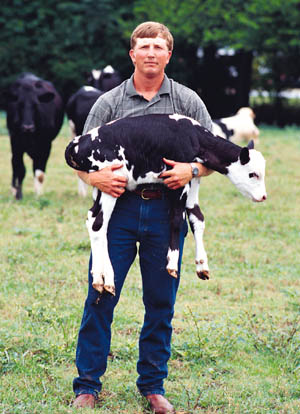

Outstanding Young Farm Family – Dairy

If Laird Cole was a real estate developer or computer programmer, his name might already be associated with towering skyscrapers or a Fortune 500 company. Because like Trump and Gates, this Hale County young farmer has a clear vision of what he wants to accomplish and the drive to make that dream a reality.A fourth-generation dairyman, Laird, 26, got his first taste of the farming at an early age when he used to help his father, Henry, put up silage. Then, in 1985, economic pressures forced Henry to sell his dairy herd and take a job in west Alabama’s emerging catfish industry.Laird, however, never gave up on the idea of owning a dairy. After high school, he raised beef cows while working full time at a catfish farm–biding his time until he could get back into the dairy business. That day finally arrived in June 1996 when the owner of a small dairy farm–not five miles from where Laird was raised–decided to sell. Laird sold his beef cows, took out a loan and plunged head first into dairy farming. At the time, he had 90 cows, 15 bred heifers and one part-time employee. Laird has since expanded the herd to 250 cows and 90 bred heifers, and today calls his business Foundation Farms.”When I got started, I had a few cattle and a few fish; I did custom hay bailing, and I had a public job,” Laird explained. “I decided all of those would be the foundation for my success.”But if Laird’s first business ventures were the financial building blocks for his dairy, the experience of his father and grandfather were the mortar. Displayed on the walls of Laird’s office are photos from when Laird’s grandfather was named outstanding dairyman in 1965 and when his father won a similar award in 1974. The newest plaque, however, belongs to Laird, who was named this year’s Outstanding Young Farmer in the dairy division.But Laird isn’t resting on his laurels. Later this month, he will complete an expansion of the dairy barn that will more than double his milking capacity, and by December, he hopes to have finished a covered “hospital” area for treating sick and pregnant cows. He also has broken ground on an 18,000 square foot equipment shed and workshop, which he plans to build next year.”We are milking in a double-four parlor now, and we’re putting in a double-10 (system),” Laird said. “Instead of milking 35 cows an hour, we will be able to milk over 100 cows in an hour. That will cut down on labor costs and give the cows more time to be out resting instead of standing on concrete.” Laird said the new milking parlor also will allow him to measure each cow’s daily milk production and send the results directly to his computer. Currently, Laird’s 305-day rolling herd average is about 17,000 pounds of milk per cow, per year. That’s up from 13,000 pounds just six years ago.He credits good nutrition and herd health management for the increased production. Laird feeds his cows a ration of hay, corn, cottonseed, cottonseed hulls and a 17-percent protein pellet. The cows are fed in an 80 x 225-foot free-stall barn that Laird constructed two years ago. To ensure the cows stay healthy and productive, they are washed at the back of the barn before entering the milking area, and he treats any foot or udder problems immediately. “I’m here every day, and I know what problem a cow is having as soon as it starts,” Laird said. “The best thing to do is to treat them right then. One thing I stress is cleanliness and getting things done right.”Another thing Laird stresses is the importance of keeping replacement heifers. He tries every heifer born on his farm in the dairy barn at least once. If she doesn’t milk at least 35 pounds a day and doesn’t breed back, she’s culled. Otherwise, she stays in the milking herd. That practice has helped Laird expand the dairy to a point that it now employs most of his family.Laird explained that his father was able to quit his job at the catfish farm and now manages the dry cows, heifers and breeding program for the dairy. Laird’s brother, Robert, also left a public job to manage the family’s 70 acres of catfish ponds and to help milk. Meanwhile, his mother, Thresa, is in charge of the baby calves, and also helps Robert and his wife, Tammy, run a catfish hatchery. Laird’s sister, Celena, is an agronomy student at Auburn University, but she also helps out around the farm by performing water quality tests as well as lagoon sampling. “The first two years, I ran the dairy by myself with just one man helping me,” Laird recalled. “Now, it’s making enough to employ all of us. This is what I’ve always wanted to do–run a dairy with my dad. It took a lot of years, but we finally made it back.”