Public Ag Research Funding Vital Despite Decline

By Marlee Jackson

While a glance around many U.S. farms yields a picturesque view — giant tractors, grazing livestock and green fields — a second look shows the impact of decades of public agricultural research.

But advancements like GPS technology, high-quality beef and drought-tolerant seed could stall if stateside research dollars continue declining while competitors amplify spending.

“When ag tends to be doing well, when technology is advanced…we dial back on overall public sector expenditures,” said American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) Economist Bernt Nelson. “It’s difficult to measure private sector expenditures, but we’re seeing those shift, too.”

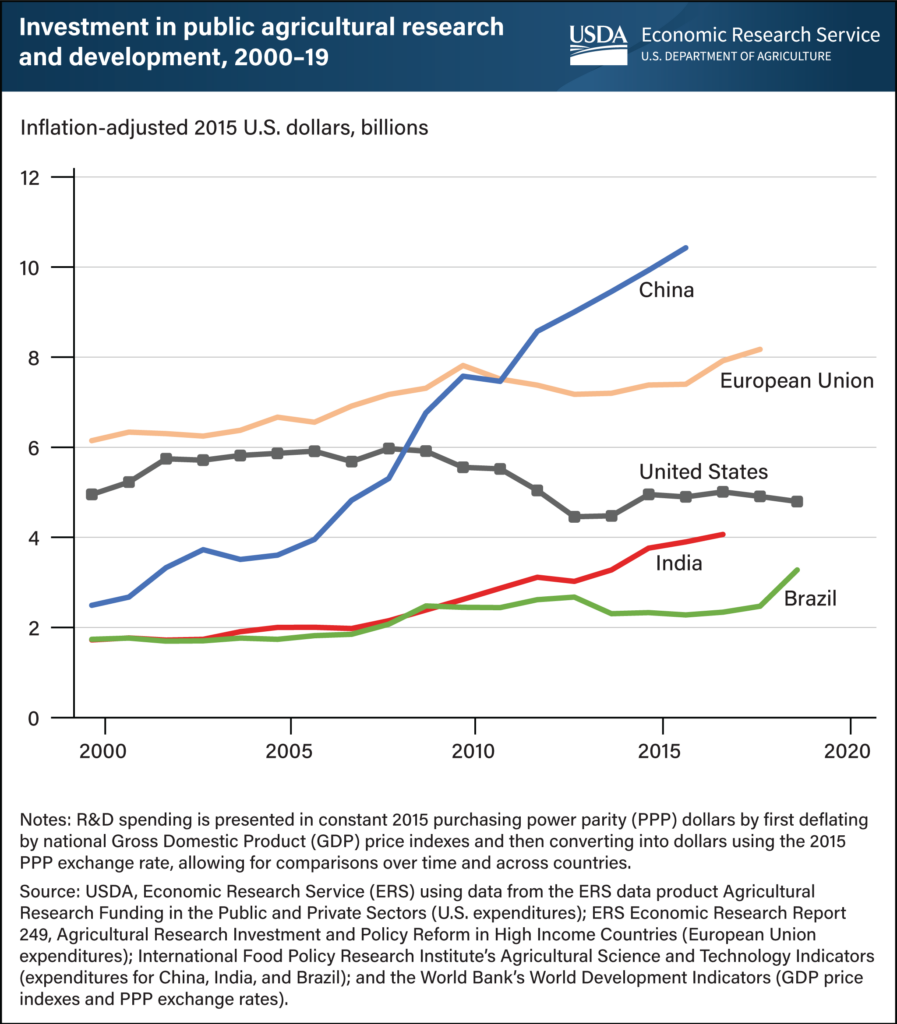

Public agricultural research and development (R&D) in the 20th century averaged $20 in benefits for every dollar spent, per the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). R&D expenses have dropped by a third since 2002’s peak of $7.64 billion.

Meanwhile, countries like Brazil and India have maintained or increased spending. Then there’s China, which catapulted past competitors.

China spent more than $10 billion on agricultural R&D in 2015. That’s double U.S. expenditures that year and quadruple China’s own R&D spending at the turn of the century.

Land-Grant Connection

Land-grant institutions like Auburn University (AU) perform about 70% of U.S. public agricultural R&D. That work is funded through a melting pot of resources and hinges on base funding through Title VII of the farm bill.

Land-grant research also relies on a mandatory state match, grants and private partnerships, which range from high-profile companies to farmer-funded checkoff programs.

Combining resources yields practical results, said AU College of Agriculture Dean Dr. Paul Patterson.

“The research topics are defined by the funding agency or company and are developed to respond to the needs of farmers, consumers, communities and businesses,” said Patterson, also director of the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station. “Research can lead to higher-yielding plant varieties, improved crop and animal management strategies or cleaner water, along with many other benefits.”

Declining research dollars isn’t the only issue, Patterson said. Sixty-nine percent of U.S. land-grant research and education facilities are at the end of their life cycles, per research firm Gordian.

Substantial investments were made in facilities post-World War II, Patterson said, as many veterans sought university careers. That Greatest Generation of scientists, housed in high-tech facilities, propelled the U.S. to global leadership in technology, science and agriculture.

Many of those facilities, including Auburn’s Funchess Hall, are still used today. Research conducted within Funchess includes agronomic and horticultural work with implications on farmers’ bottom lines.

Funchess was built in 1960.

“Simply put, 21st century science cannot be performed in a building built in the middle of the last century,” Patterson said. “Modern research instruments do not perform well in aging buildings with unstable environmental conditions.”

To help remedy the issue — and attract top-tier faculty — Auburn is replacing Funchess with a STEM+Ag Complex. The 265,000-gross-square-foot lab and office building is funded through state support, AU bonds and private contributions. It’s a prime example of compiling funds to advance agriculture, Patterson said.

Farm Bill Funding

Meanwhile, D.C. decision-makers are crafting the 2023 Farm Bill, which impacts research and Extension funding.

AFBF and Alabama Farmers Federation policies support public funding for agricultural R&D, said the Federation’s Mitt Walker. While increasing Title VII funding is ideal, maintaining current levels is crucial.

“Public research is that critical connection between the technology companies develop and getting proven results to farmers who need it,” said Walker, who manages national affairs. “We have to move forward so we don’t get left out of the global marketplace.”