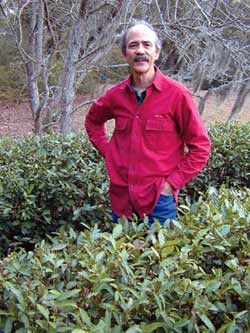

Tea for Two – Baldwin County Couple Finds Joy in Growing Tea

Kicking back in the kitchen of his homey Barnwell farmhouse, Donnie Barrett pours a visitor an amber glass of sweet tea and sips his own glass of homemade satisfaction.”My tea is very similar to black tea, but it is distinctively more flavorful and less bitter,” Barrett said, taking a taste of the brisk beverage brought to perfection after more than two decades of trial and error.Barrett–a Fairhope native better known as a historian, archeological preservationist and curator of the Fairhope Historical Museum–also is the owner of the little-known “The Fairhope Tea Co.”Since he planted his first tea plants 23 years ago, Barrett has tapped into the trade secrets of growing tea and become an expert on planting, processing and propagating his own unique blend.Working alongside his wife, Lottie, and his family, Barrett turns his home south of Fairhope near Weeks Bay into a tea factory several times a year. He sells his Hurricane Blend–a part black, part-green tea, called an oolong style, with roots in a crop destroyed during Hurricane Frederic in 1979–over the Internet.But he hopes to market his beverage locally someday soon. “That is what I envision: seeing my tea being sold in downtown Fairhope shops,” he said, his mustache turning upward into a smile.In addition to reveling in his history and raising some 50 rare peacocks and guineas at his farm, growing and cultivating great tasting tea is Barrett’s other obsession.Fueled partly by passion and partly by a healthy caffeine buzz, Barrett rattles off all he has done to get to the glass of tea he drinks today. His commitment can be defined by the time he has invested in his hobby and the distance he has traveled to quench his thirst for tea’s coveted trade secrets.Out of the ashesBarrett’s love affair with tea goes back to his childhood.”As Southerners, we were big tea drinkers, and that got me focused on tea,” he said. “People say they drink tea year-round, and so do I.”Barrett had never seen a tea plant, though, until 1977 when a tea company planted some camellia seninsus plants at the Auburn Experimental station in Fairhope, where Barrett’s father worked as superintendent. “I admired those plants, and I thought to myself at that time, ‘Tea. How unique. Everybody drinks tea but no one knows anything about it,'” he said.Two years later in 1979, Hurricane Frederic destroyed that crop. “The hurricane just blew them into a pile,” Barrett said. “So the company pushed them into a pile and burned them.”When the tea company left Fairhope, Barrett scavenged the few plants they left behind. The next day while he was helping his father and others clean up the mess, Barrett noticed some green plants sticking out of the charred pile.”I found three plants in the burn pile and pulled them out and put them in my parents’ yard,” he said. “I watched over them and took care of them, and in about a year, those three plants produced 1,000 plants.”Barrett has since crossbred the three varieties and after years of work, has propagated his own variety that he is producing by the thousands and planting in rows out in the fields and in a greenhouse near his home. The prickly hedges represent years of research. For years, Barrett’s quest for information on growing tea plants was less than refreshing.When he wrote tea companies asking for information on growing and making tea, those companies sent him press releases saying they could send him samples of their tea, Barrett said.Finally, an Internet search led Barrett to a Virginia man who manufacturers tea tags. The man explained why Barrett was being stonewalled.”He told me, ‘These are family secrets; they are trade secrets cultivated over generations, and they are not going to tell you,'” Barrett said.So five years after his search began, Barrett turned to the Chinese, the leading tea producers in the world, to unveil those secrets.While in China in 1984, Barrett learned the best way to grow and process tea, he said. But it would be another decade before his tea would come out full-bodied and fragrant, he said.”The Chinese showed me how to make tea,” he said. “But it took me 10 years more before I could make it aromatic and not flat.”‘Tortured’ teaOne thing Barrett learned from the Chinese and from his own experience is that tea likes to be “tortured.””It is a real funny plant,” he said. “It is a very competitive plant. They do best when you plant them on top of each other, and they like any kind of soil. You have to torture and torment them by cutting them way back and shading them. They love black plastic. Any plant would die from black plastic, but they love it.”Barrett practices an orthodox tea-making process that tends to be labor intensive. “It is referred to as the best way to make tea, but it is expensive,” he said. “It is all done by hand and has several steps.”Barrett keeps his costs low by recruiting his wife, and sometimes his family, to pick the tea in spring and process it all summer long on his front porch. Processing the plant is not his wife’s cup of tea, but she supports her husband nonetheless, he added.”She would rather I sell the tea company,” Barrett said. “But she works right alongside me because she knows I care about it.”After the tea leaves are picked, the tea is put in bags and rolled or beaten on the floor so the veins in the leaves are smashed, distributing the plants digestive juices throughout the rest of the leaf. The process digests the sugars and starches in the leaves, Barrett said.Then, the leaves go through a blacking process whereby the green leaves are allowed to turn black. “We watch it and smell it and have to catch it before it mildews or molds,” Barrett said.Next comes the drying process. Barrett spreads the leaves on blankets out in the sun for several days in an attempt to stop the blacking process and kill any mold or mildew that might have grown during blacking. The dry crunchy leaves are then rolled up and stored for a day or so until they can be toasted during a firing process.Barrett cooks the leaves in an outside oven until they almost start to burn. The firing process oxidizes the leaves making them flavorful and aromatic, he said. The next part of the process is called screening. It removes sticks and stems from the tea plant.Finally the tea leaves are ground up in a food processor to just the right consistency. “If it is too fine, you will have too strong a tea,” Barrett said. “If it is coarse, it is easier to store and it usually takes three tablespoons of tea, steeping at five, six or 10 minutes to make a great tea.”Nothing to loseThe tea-making process has Barrett up all hours of the night in the summers. The hours are awful, the work hard and the pay minimal.But Barrett keeps dreaming of the day when he will take the plunge into selling his tea locally. Barrett has no plans on quitting his day job of 28 years as a graphic artist for Print Xcel of Fairhope, a business forms manufacturer. It’s a job he loves.But, he said it is fun to balance the desk job with farming a crop so unique. “I get satisfaction everyday from it,” he said.He is optimistic that Fairhope residents and tourists to the bayside city will want a taste of his local, time-perfected treasure. If so, it will be sweet satisfaction for Barrett, who contends the odds are in his favor. “I can’t lose because I haven’t invested anything,” he added. “Besides, I think I am on the right side of supply and demand because everyone drinks tea, and no one is making it.”Whatever happens, he looks at the venture with a “glass is half full” outlook.”I am a very positive person,” he said. “I work as hard as I possibly can. I have worked at it everyday.” Freelance writer Lesley Farrey Pacey lives in Fairhope. This article originally appeared in the March 4, 2002, issue of the Mobile Register. Courtesy of the Mobile Register 2002©. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.